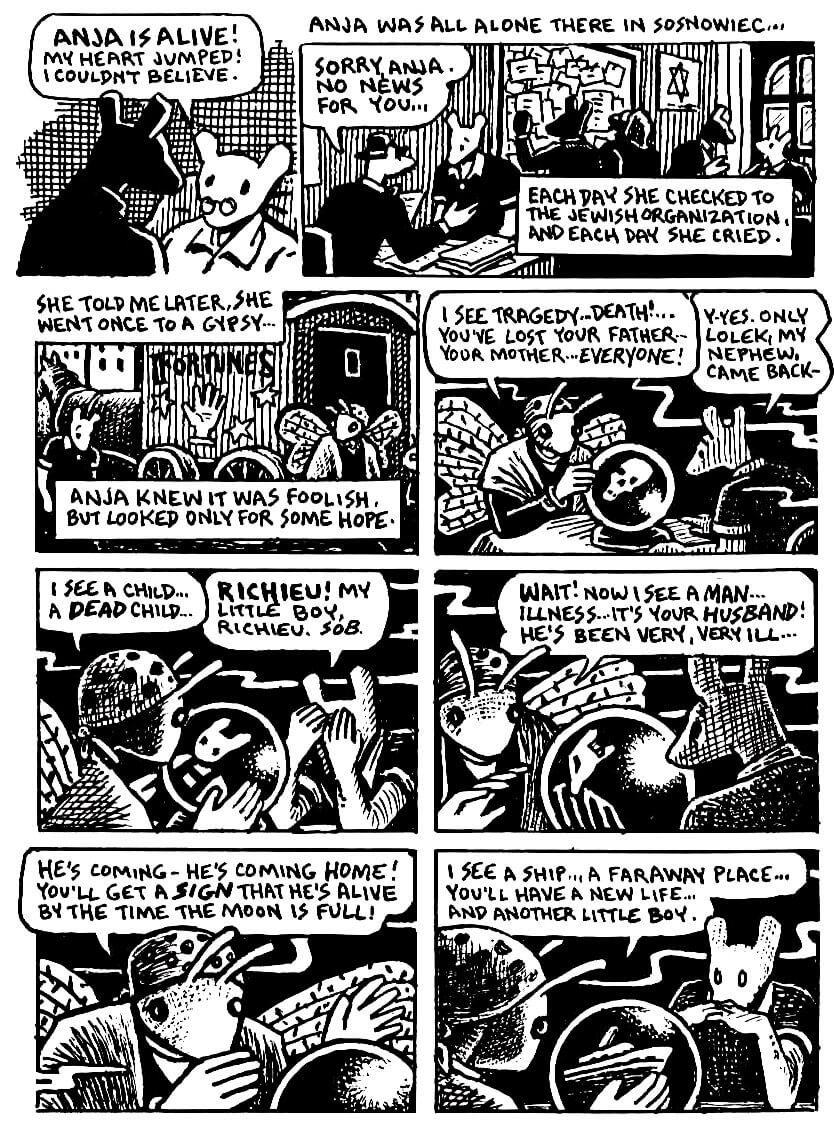

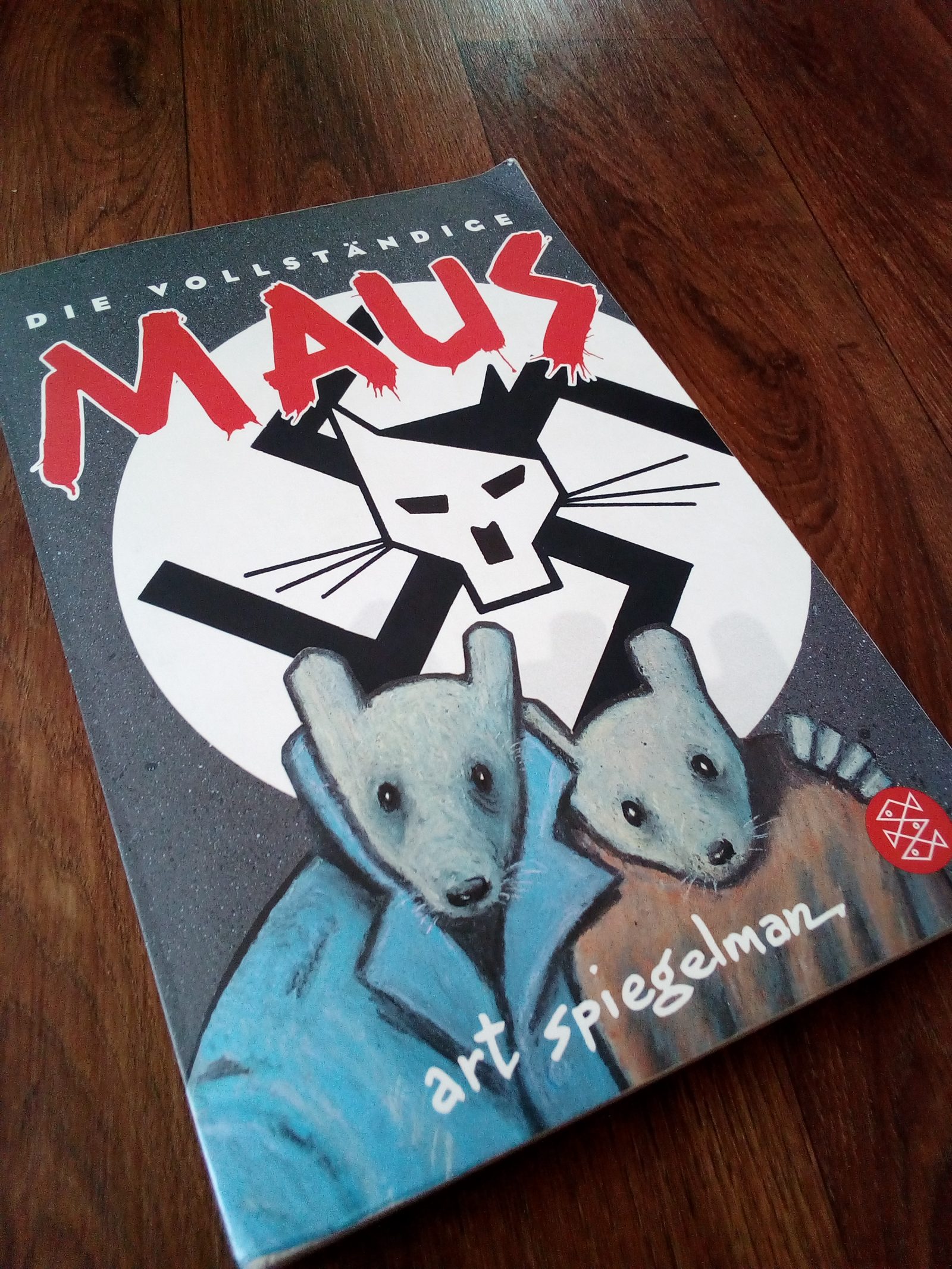

At one point, a board member seemingly singles out a striking scene in Maus I, where Vladek sees four Jews, executed for trading on the black market, hanging on a central street in the Polish city of Sosnowiec in 1942. The meeting minutes from the McMinn County school board are especially telling. Read: The banned books you haven’t heard about These aspects, while perhaps not ideal for an eighth-grade audience, feel beside the point in a narrative that bears witness to genocide. The board cited bad language (such as “bitch” and “goddamn”) and nudity (specifically, one small image of Spiegelman’s mother, drawn in human form, in the bathtub after taking her own life, a profoundly troubling visual on which to pin the charge of obscenity). When the book emerged as a fresh target in the culture wars this year, the school board’s official, and flimsy, reasons for removing it from the curriculum amplified the outrage. Maus was also subject to book burnings in Poland in 2001, the year it was published there (long after other foreign editions), by people who objected to its depiction of Polish gentiles. It was notably banned in Russia in 2015 because the modified swastika on its cover was categorized as violating anti-Nazi-propaganda laws. Maus is also a tricky text, prone to misinterpretation-and, as in Tennessee, censorship. The drawing allows Spiegelman to do more than say what happened. This level of abstraction, which repurposes a metaphor from Nazi propaganda, is hard to imagine being effective in any other medium.

MAUS GRAPHIC NOVEL SERIES

The series famously articulates its characters as animals they understand themselves as human, but readers see Jews as mice, Nazis as cats, Polish gentiles as pigs, and Americans as dogs. The critic and journalist Alisa Solomon, for instance, notes in her 2014 essay “The Haus of Maus” that the book “became the proof text for academic study of the transgenerational transmission of trauma and its representation.” It also is a high-water mark for comics-exemplifying the medium’s productive tensions between word and image, presence and absence, that are so key to expressing memory. Maus’s importance cannot be overstated: It shifted how people talk about history, trauma, and ethnic and racial persecution. This article is adapted from Maus Now: Selected Writing, edited by Hillary Chute. One of Spiegelman’s longtime catchphrases-“Never again and again and again”-feels eerily prescient he gave what he calls “ Maus Now” talks after the fatal racist, white-nationalist Charlottesville, Virginia, rally in 2017 (which included the chant “Jews will not replace us!”), and the Tree of Life synagogue shooting in Pittsburgh in 2018. In fact, a work like Maus could not be any more urgent during an era of rampant division, one in which racism and anti-Semitism are rising both nationally and globally. Of course, that confrontation with horror is exactly what makes it valuable. And Maus’s frank visual depiction of horrors, the way it acts as a form of witness to dehumanization and genocide, is controversial. A new wave of politically driven censorship, particularly one motivated by a discomfort with discussions of America’s history of slavery, has grown in the Trump and post-Trump years. Read: Book bans are targeting the history of oppressionīut the ban didn’t surprise me. The ban became a global news story Maus sold out on Amazon. This came to wide attention this past January, when Maus was banned from an eighth-grade English-language-arts curriculum by the McMinn County, Tennessee, school board. It is, in addition, taught to many middle-school students. It is taught routinely in high school, college, and graduate school. In black line art, it presents two narratives: the story of Spiegelman’s father, Vladek Spiegelman, a Polish Jew who survived the Holocaust and immigrated to the United States in 1951 with his wife, Anja, also a survivor, and their toddler, Art-and the story of the cartoonist son, as an adult, soliciting his father’s testimony. (He got up in the middle of the same event and went outside to smoke a cigarette, leaving me facing an empty chair, and a packed house.) It’s true that Spiegelman “speaks”-and draws-the unspeakable in Maus. “For one thing, the unspeakable gets spoken within 10 minutes, by me if nobody else,” Spiegelman quipped.

“Maybe vulgar, semiliterate, unsubtle comic books are an appropriate form for speaking of the unspeakable.” It came to him around the time he started making comics about the Holocaust, which would eventually lead to his two-volume, Pulitzer Prize–winning masterpiece, Maus: A Survivor’s Tale.įorty years later, at an event where I was interviewing him, I asked about that quote.

“Maybe Western civilization has forfeited any right to literature with a big ‘L,’” he wrote. In the 1970s, the cartoonist Art Spiegelman jotted down a thought in a notebook.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)